One day in 1992, Zhang Huan, a student attending a university in Beijing, went for a bike ride. As he rode around, he stumbled upon a mannequin’s leg: A woman’s leg. No body, no arms, no other leg. Something about the strange object caught his eye. He picked it up, brought it to his studio in the Beijing East Village, and began playing around with it, eventually taping the leg to his own body. It was a radical moment for Zhang, for he began to see the human body as an artistic element.

“I can say that all my relationship with performance…can be traced back to that episode,” he said in a 2005 interview.

Zhang Huan, born in 1965 in Anyang City, Henan Province, China, has had a long, distinguished career. He’s had solo exhibitions all over the world and has worked as a painter, set designer, photographer and sculptor. He also claims to have coined the name for the prominent 1990’s Chinese artistic community known as the Beijing East Village.

In contrast to his humble beginnings, recently he has been able to live abroad and employ more than a hundred assistants at a time. But it was his outlandish, body-centered performance art pieces from the ‘90s that have left the greatest mark in public and critical imaginations.

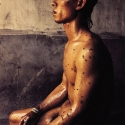

A few of his notable performance art works from that period include “12 m2,” a 1994 performance for which Zhang smeared his body with fish oil and honey and sat naked in a filthy, fly-infested public bathroom for three hours; his 1995 piece “To Add One Meter to an Unknown Mountain,” for which people laid naked on top of each other in order to add a meter to the mountain’s height; and 1997’s “To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond,” for which Zhang and his assistants stood naked in the Nanmofang pond in order to raise the lake’s water level.

There have been political readings of Zhang Huan’s work. However, the artist has instead repeatedly emphasized his work’s physical and spiritual dimensions. As he told Art Journal in 1999, “The contact of…iron chains, ice, sparks, flies, and earthworms with my naked body makes me feel my body more strongly and helps me to develop a deeper understanding of the body.”

During the last few years, his work has taken a religiously iconic direction, related to his conversion to Buddhism.

In looking at photos of his art, a single quality might explain Zhang’s popular appeal beyond conceptual art circles: much of his work bears a kind of brute, aesthetic beauty that goes beyond its conceptual framework.

Written by Patricio Maya